Earlier this week on Twitter, Carl Richards (+Behavior Gap) -- who you really should be following if you're not already -- started an interesting conversation about investing and risk:

As Homer Simpson would say: "It's funny 'cause it's true." And for two reasons. First, and most obviously, because statistics can be confusing and second because the industry's statistical definition of risk is too academic and doesn't get at the root of what keeps investors up at night.

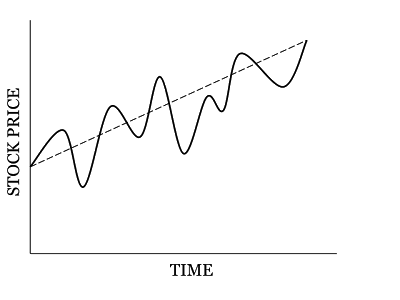

Finance textbooks and trading models might define risk in statistical terms based on volatility, but such definitions are incomplete for patient, business-focused investors.

If we've done our homework, purchased a stock at a good price, and remain confident in our thesis, how the quoted stock price moves on a day-to-day or month-to-month basis shouldn't be of any concern. You'd be hard pressed to find an investor who cared about the following type of volatility:

Different definition

Instead, what long term investors are really concerned about is permanent loss of capital. As the name implies, a permanent loss of capital differs from a temporary loss of capital that's due to market volatility and it occurs when an investment's value has declined so much that getting back to break-even within a few years is unlikely. Effectively, an unrecoverable loss.

As the following table shows, when a stock loses 40% or more of its value, it takes a substantial recovery to get back to even:

To put this in some perspective, consider a 50% paper loss on an investment. While it's certainly possible for the stock to stage a huge recovery and double in value over the next year, if we assume historical equity returns of 9% per year, it would take about eight years for the stock to get back to even on a nominal basis.

Though you might patiently wait for this to happen, that investment from eight years prior was in essence wasted capital that could have been invested more effectively elsewhere.

How to avoid such a fate

Invest long enough and you'll have a permanent loss of capital at some point. It's bound to happen as we're all human, but it's critical to make large losses infrequent events as they can seriously weigh on your portfolio's long-term returns.

Here are five things you can apply to your investment process to reduce the likelihood of permanent losses of capital:

1. Buy with an appropriate margin of safety. This may seem obvious -- buy a stock for less than it's worth and you'll reduce the odds of permanent losses -- but (a) we as investors are prone to buying into stories, individual attributes (high yields, low PE, etc.), or a hot tip and fully disregarding valuation and (b) when we do adequate valuation work we often make inappropriate margin of safety assessments before buying.

What I mean by the latter point is that we should demand a larger margin of safety when buying a business with a higher degree of uncertainty and vice versa. It's one thing to buy a large cap defensive company like Coca-Cola with a 10% discount to fair value, but a 10% margin of safety isn't likely enough for a small-cap stock in a cyclical industry. You're more likely to lose your shirt feeling too confident in your assessment of the small-cap's value than you are of Coca-Cola, so a larger margin of safety is required.

The important point here is that checklists can save us from making stupid decisions based on emotion. For more checklist ideas, +Stockopedia has a great set of checklists based on different styles of investing.

Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital calls this "second-level thinking". In his book The Most Important Thing, he provides the following example:

First-level thinking says, "It's a good company; let's buy the stock." Second-level thinking says, "It's a good company, but everyone thinks it's a great company, and it's not. So the stock's overrated and overpriced; let's sell."Each investment will have specific questions to ask, but if you're looking for a good place to start, here's my list of five questions to ask before buying a stock.

4. Focus on trends in competitive advantages. The market has become incredibly focused on the short-term. For example, the average stock mutual fund turnover rate have jumped from an average of 17% between 1945 and 1965 (implying an average holding period of about five years) closer to 100% today (implying an average holding period of about one year). Naturally, then, market participants seek short-term information advantages -- e.g. "Will this company beat next quarter's consensus estimates?" -- at the expense of gathering helpful long-term information.

In his book More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places, Michael Mauboussin notes:

My fear is that much of what passes as incremental information adds little or no value, because investors don't properly weight information, rely on unsound samples, and fail to recognize what the market already knows. In contrast, I find that thoughtful discussions about a firm's or an industry's medium- to long-term competitive outlook are extremely rare.Spend more time in your research process thinking about where this company might be three- to five-years from now. A simple way to get started is with a "SWOT" analysis -- listing the company's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Then ask how the company might enhance its current strengths, reduce its weaknesses, capitalize on opportunities, and respond to competitive threats.

5. Avoid cult stocks & sectors that are in the market spotlight. Jason Zweig had a great post for the WSJ this week on his mission to save investors from themselves by helping them avoid speculative periods in the market. Also the commentator on the revised edition of Benjamin Graham's Intelligent Investor, Zweig has the rare ability to spot market irrationality and stand behind his convictions even when they're not popular at the time.

The perennial refrain from critics is: You just don’t get it. Internet stocks / housing / energy prices / financial stocks / gold / silver / bonds / high-yield stocks / you-name-it can’t go down. This time is different, and here’s why.But this time is never different. History always rhymes. Human nature never changes. You should always become more skeptical of any investment that has recently soared in price, and you should always become more enthusiastic about any asset that has recently fallen in price. That’s what it means to be an investor. (My emphasis)

Bingo. Can't say it any better than that. Consistently follow this advice and it will help you avoid permanent losses of capital.

Bottom line

The best definition of risk for long-term investors isn't volatility, but permanent loss of capital. Every investor will have permanent losses over his or her investing career, but the key is to minimize their frequency. Hopefully these five suggestions will help you avoid some of them.

Good reads/videos this week:

- Howard Marks on the proper definition of risk (a must-read)

- The aforementioned Carl Richards on avoiding behavioral investing traps (video)

- Michael Mauboussin on the roles of skill and luck in investing (video)

Have a great weekend!

Best,

Todd

@toddwenning